Syun- Ichi Akasofu has a new article ("On the recovery from the Little Ice Age", Natural Science Vol. 2, No.11, 2010) which is likely to be influential in the pseudo-debate on Global Warming, if not on the actual debate. The reason I do not think it will be influential amongst scientists studying Global Warming is the purpose of this post.

Before getting to the meat of my critique of Akasofu, let me first puncture his key rhetorical device. That rhetorical device is, of course, his reference to a "recovery" from the Little Ice Age. Of course, a "recovery" is not an explanation of a change in temperatures. The only possible explanation of a change in temperatures is a change in energy flows; and without such energy flows, there is no innate temperature that the Earth's mean temperature will recover towards if perturbed. Climate is not a pendulum.

Talking about a "recovery" does punch all the right buttons. It sounds like a natural thing, a thing that we would expect, something for which we require no further (anthropogenic) explanation. But "sounds like" is not the same as "is". "Recovery" is just a place holder for an explanation, not an explanation itself. Disapointingly, when we come to Akasofu's actual explanation of late 20th century warmth, it turns out to be just another variant of "it's the sun", an explanation repeatedly considered, and rebutted by climate scientists. So what Akasofu offers us here is not a new idea, but just some new clothes for an old one.

Having said that, what evidence does Akasofu present that the recent temperature increases are just a "recovery"? It turns out to be surprisingly thin, and distorted. I say distorted, because time and again he shows isolated examples rather than robust selections of the data. And the data he shows is curiously truncated. For example, the data he shows on arctic sea ice extent (figure 2 d) curiously truncates in 1998. One would think an article written in 2010 would have included sea ice data from 2007, but that data somewhat spoils the picture Akasofu wants to paint.

One such distorted data presentation is the choice of only GISP2 to show holocene temperature data before 800 AD (figure 5) :

(The bottom half of Akasofu's figure 5)

The temperature range over the Holocene is a critical issue to Akasofu's argument. He is arguing that the temperature rise to 2000 is just a recovery from the LIA, but a recovery is just a return to previous normal values. As such, for his argument to hold water, he must show that temperatures around 2000 AD were typical of, or lower than temperatures prior to the LIA. And the GISP-2 data certainly appears to support that contention, with the temperature at 0 years before present (1950 by convention) being approximately 1 degree C below the mean of the GISP-2 data, and 2.5 degrees below the peaks. Even warming subsequent to 1950 has not lifted global temperatures above this mean.

However, when we compare the temperatures indicated by a range of proxies from around the world, an entirely different picture emerges:

(Holocence temperature variations from wikipedia, follow link for key)

The thick black line is just the arithmetic mean of the proxies, and as such not a true reconstruction of temperatures. It is, however, a far better indicatorr than just taking one site at random. Based on that indication, global temperatures have shown a long term decline over the last 8,000 years, with the mean temperature at the end of that period being about 0.25 degrees below that at the start. Based on this, more complete information, we would expect a "recovery" from the LIA to have lifted temperatures to about that mean, ie, around 0.7 degrees C less than they currently are.

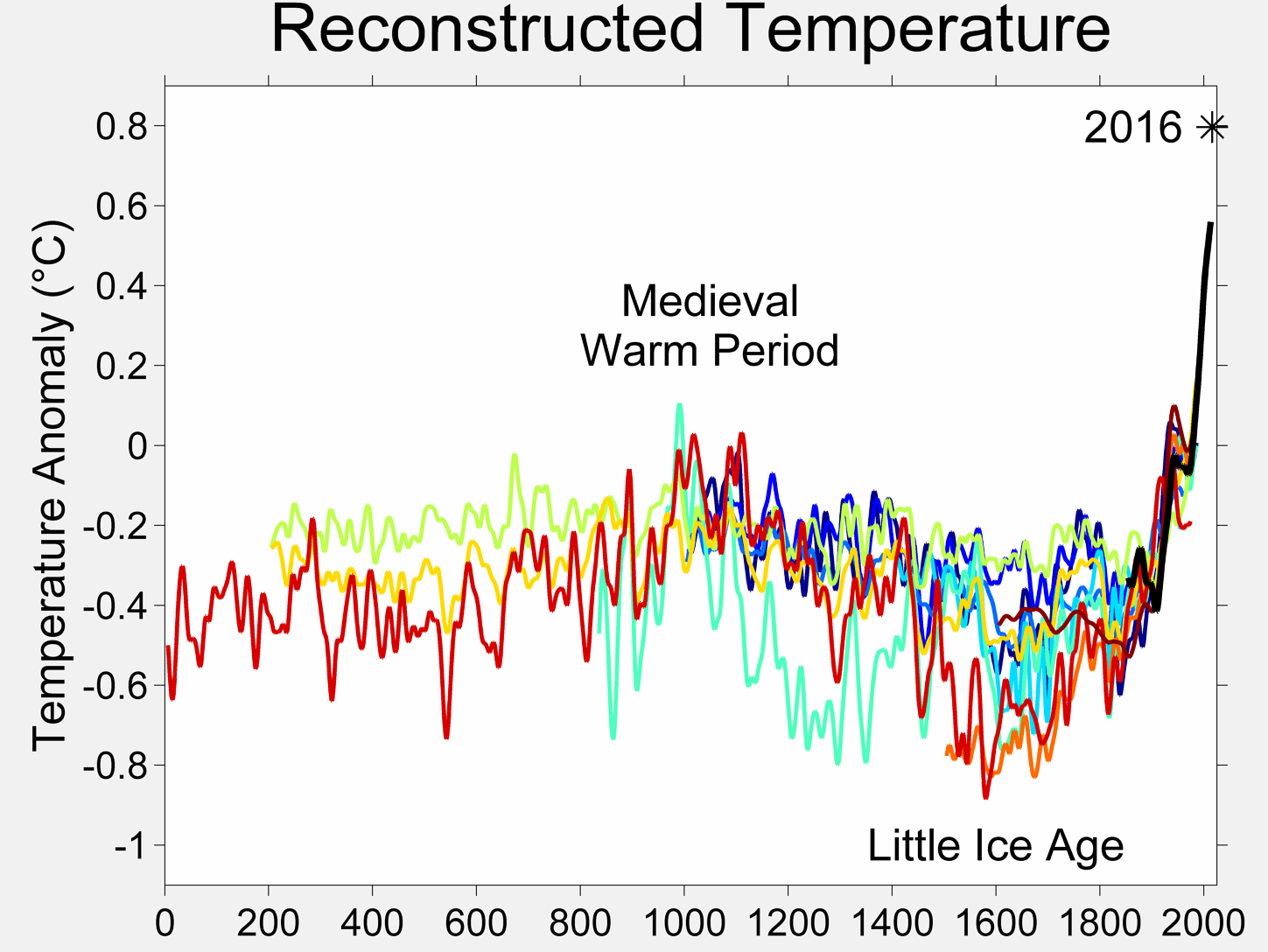

Focusing in on a tighter picture makes the distortion in Akasofu's chosen data even more apparent:

Temperature reconstructions for the last 2000 years, follow link for key)

Based on temperature reconstructions over the last 2000 years, we see the average temperature over that period to be around 0.2 degrees below the 20th century mean. Looking closely, we discover that Akasofu's "recovery" has lifted temperatures as far above that mean as the LIA ever took it below it. It turns out that "recovery" is a word that, however reassuring to Global Warming sceptics, is very inapt as a description of the temperature changes over the last 200 years.

An additional argument by Akasofu is that temperature trends since the end of the LIA are best represented by a linear trend of 0.5 degrees C per 100 years, overlaid by an oscillation with a period of around 60 years:

(Akasofu's figure 9)

This claim appears to be born out by the figure above, as also with several other figures Akasofu presents, all terminating in the late 19th or early 20th century. In the example above, the temperature graph starts in 1880, just 30 years before the first minimum on the graph, and hence on Akasofu's theory, at a maximum. Astute observers might be suspicious of the theory in that the 1910 minimum barely lies below the trend line. In fact, given the balance of temperatures above and below the trend, we can see it was not drawn by mathematical analysis of the data, but merely to suite a particular theory.

Our suspicions about this graph are confirmed, however, when we consider a longer temperature record:

(Temperature data from CRU, UEA)

The HadCRUt3 index of global temperatures extends the instrumental temperature record back to 1850. That is 30 years, or another half cycle prior to the start of the temperature record used by Akasofu, and represents an ideal test of his theory. According to that theory, we would expect the temperature in 1850 to be at a minimum in the cycle, and therefore to lie below, or at least very close to the trend line. Instead, it lies as much as 0.5 degrees C above it. Given that the amplitude of the cycle is approximately 0.3 degrees, that fact conclusively disproves Akasofu's theory.

In fact, if we look more closely, we see that while there is still an oscillation present from 1850 to 1910, the overall trend is a slight cooling. If we take of the blinkers and examine the trend for each cycle separately, we can see that underlying trend from 1910 to 1970 is less than that suggested by the "peak" in around 2000. So the instrumental data, in full, shows first a cooling trend, then a warming trend, and over the last 30 years, an even stronger warming trend.

Akasofu also tries to support the idea of a linear warming trend since the end of the LIA with data on glacier lengths. To do so, he shows us pictures of glacial terminations at different locations for four glaciers. He also shows us the graph of fluctuations in glacial length of one particular glacier, a graph that again appears to support his case:

(Akasofu's figure 3f)

In this case, the appropriate comparison is to the global glacier mass balance for mountain glaciers:

(Global Glacier Mass Balance from Skeptical Science)

When we consider not just one glacier, but all; and not just glacial length, but thickness as well (and hence volume) we see the picture that emerges from Akasofu's one graph is not typical at all. Rather than one, more or less continuous reduction in glacial length since the end of the LIA. we see a long period of relative stasis, the first part of which coincides with the slightly declining global temperatures seen above. Only since about 1970 have glaciers started losing mass in a significant way. Akasofu's picture of one continuous trend is again seen to b e unsupported by the full range of data.

There are other pieces of data presented by Akasofu in support of his contention that the current warming is just a recovery from the LIA. However, the other evidence suffers the same deficiencies seen above. His linear trends aren't linear, and his data is never the most extensive, or the best available to analyse the evidence. Rather, it is data that appears to support his case - when the more extensive data does not.

(Continue to Part 2)

(Continue to Part 3)

As a lay person, I am a fan of this article.

ReplyDeleteI ran into this claim on curryja. On a graph that showed the results of 55 climate model runs, skeptics were demanding to know if one model had correctly predicted the results of 2000 to 2009 (not a demand of climate models that I would consider especially reasonable.) I pointed out that the models appeared to have predicted 2000 to 2009 would be warmer than the previous decade. A commenter said that prediction was worthless because the earth was naturally warming since of the LIA, and, basically, a monkey could have made that prediction. So I asked what was naturally warming the earth since the LIA (until present.) A former NASA scientist jumped all over me for being ignorant of natural cycles of the past (I've read a great deal about them,) and then mentioned the sun and oceans, of which I am somewhat aware. So anyway, I went to wood for trees and graphed the temperature record from Arrhenius's birth until 1896, and somehow I don't think he thought he grew up in a world that was naturally warming to an extent even remotely like the rate of my life. Imo, Arrhenius probably thought CO2 warming would be beneficial because he grew up in a pretty cold world. In 1899 my Grandfather could have skated from St Louis to New Orleans. That was one of his themes; he grew up in a world that got progressively colder; his lucky grandchildren were growing up in a world he knew was warmer. 1899 was the first year of his life in which he could have skated from St. Louis to New Orleans.

I should have asked if any scientists prior to the modern emergence of AGW had predicted the natural warming since the little ice age would result in 2000 to 2009 being warmer than the previous decade (and within reasonable proximity to 2000s temperature.) I've been searching Google Scholar for that. So, prior to the modern emergence of AGW, do you know of any scientists who were making such a prediction based upon natural causes, or anything that could possibly be construed as such a prediction?